Many a thing was done about a new UXperience

— Forget everything you’ve learned. Why Vieira Pinto if we have Norman? Why hermeneutics if there are heuristics? Forget about universities. By the way, why bother with universities if we have UX courses? Why bother with advertising writing if there is “UX”? Why have art design if we have “UI”? Why care about “GRP” if even the TV is dead? All that matters is what focuses on the “user”; the rest belongs in the past…

Said the new to the old.

The Yankee’s fingerprints are all over everything that is Latino. Regarding the reporting of what’s been done, especially. I see, however, a key turn, the search for the publicist’s own work that has been trodden up to here. I demand, in history, the original engine of our dashed drawing, our creative writing, and our media research. Listening, analyzing, mediating, quantifying, and creating have always been part of advertising. Much has already been done in Latin America’s Communication and Media Research history. When returning to the past, I point out the foundation in the new facets of product research: Publicists’ (re)constitution. Also, its disseminates interferences of the technique, currently, above all, on making media product research. In this, there is a new and an old dialogue. The product is media, new. Language is media, old.

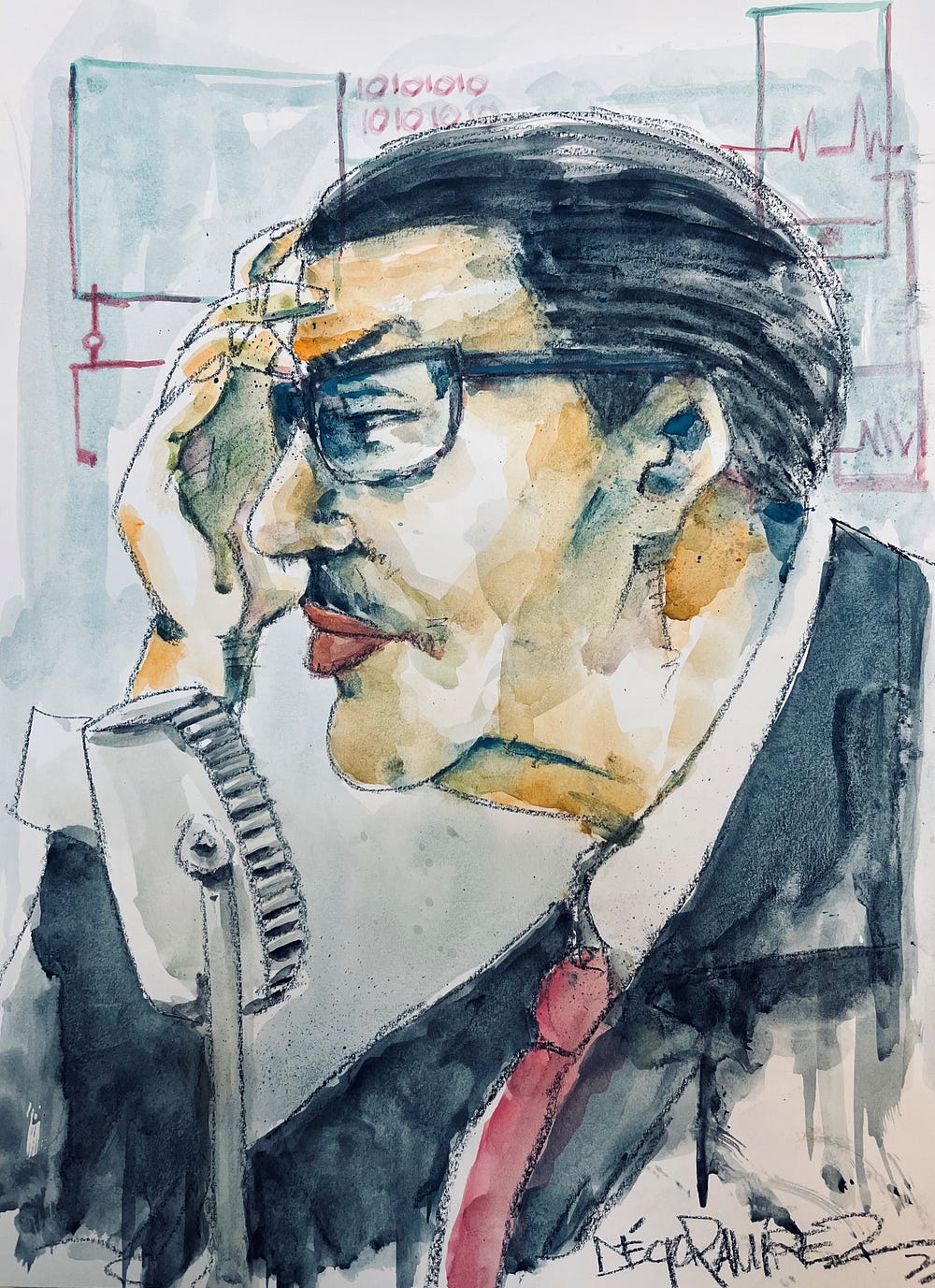

The first intervention I did in Nosso Meio compared the technical work of media professionals with “experience researchers” (product researchers/UX researchers). It had announced the tone it would set by defending in this space the momentum to underpin Publicity as an area of mastery of the meanings of the diction of the 2020s: “experience.”

I briefly highlighted the quantification that public opinion studies were based on the influence of the sociologist of communication Paul Lazarsfeld. The People’s Choice, released in the 1940s, announced the milestone that I mentioned about the qualitative and quantitative divisions in marketing and academic communication studies — a dissension that today is limited to the skills of mastering the reinvention of the advertising technique. The history will be portrayed from now on. I include, in it, the interfaces where the forces of form operate in technique.

The 1940s are very similar to those of the 2020s, especially at the dissemination stage of a new publicist practice. Richard Smith, Professor Emeritus of History at the University of California (Berkeley) 2013, published an article that signaled the beginning of the influence that until today is intertwined with the Yankee reach in research practices of Brazilian firms. He believes that 1940 was the beginning of the most systematic US diplomatic policy, the Good Neighbor Policy. In the same year, one hundred and thirty Latino publicists visited the United States to understand the way of life in that country.

The result culminated in the tourist movement of more than one hundred thousand foreigners from various nations, according to Uncle Sam’s newspaper, The New York Times (1990). Dr. Smith confirms that this expedition, the first among publicists, included Brazilians: Gilberto Freyre, Sérgio Buarque de Holanda, and Clodomir Vianna Moog. The policy was incremented by the developmental wave of national advertising formulations. Standards were established, and they didn’t stop at the “briefing” or the big companies’ brand application manuals.

It was the beginning of a narrative and creative wave for the consolidation of an America and a Latin America minimally delivered to the publicist conglomerates of the time. This wave completes 82 years of centrality in the “other,” from ethnographic expeditions to public opinion research. The future will tell the fruits of these bilateral exchanges, including the so-called “user-centered view” that dominates Brazilian corporate practices, processes, and discourses. In this history of the influence of the (re)constitution of research, there is something unquestionably Brazilian; an accent, as highlighted by the “experience researchers” Cecília Henriques, Denise Pilar, and Elizete Ignacio. It is about this supposed “our UX” that this column is about. Deep in this article that launches the Nosso UX column, elements that will strengthen this argument.

I understand, in four axes, contributions for theoretical dialogue with standard corporate practices. I bring them together as part of a whole: public opinion and experience. I call History of Experience the articulations of the supposed affinity between empiricism, experience, social interaction, and technology. It would be entitled History of Public Opinion, an “old-school” discipline and an unfortunate synonym for the sum of opinions. The “trend,” the “new” media, the “remaking” establishes it, however, as History of Experience. Every two weeks, these theoretical tensions, meeting UX practices, will be guiding us. Significantly, the “R” after the “X”: the UXR.

By Fernando Nobre Cavalcante, Ph.D.